Talking exclusion: Must it always be a school’s last resort?

In this month’s blog, Thomas Goodenough, the VRU’s new Education Lead discusses the challenges associated with discipline policies and particularly exclusion from school – challenges faced by colleagues across the education sector.

Tom was a teacher and school leader for 16 years in several schools across the Thames Valley, including headteacher of both Didcot Girls’ School and Park House School, Newbury. He has recently joined the Thames Valley Violence Reduction Unit, bringing his expertise on education and particular interest in how schools can play a part in increasing social equity. He is now working on a programme of work across the education sector and in building youth voice.

“Talk to most school leaders and they will tell you the same story when it comes to exclusion: We know it doesn’t work and nobody wants to do it. However, for a host of reasons which do not seem to be going away, we do not feel like we have any alternative options at times.

“Both inside and outside schools, opinions are often split, with some maintaining that schools must have the option of this ‘ultimate sanction’ as a deterrent, a protective measure and a ‘message’ to send about what is acceptable in a school. Meanwhile, others look at it as unfair and potentially damaging treatment to mete out to a child for behaviour they often have quite limited agency over.

“However, what is less up for debate is the correlation between school exclusion and significantly diminished outcomes (both in school and thereafter in life beyond the school gates). We know that exclusion correlates to poorer academic outcomes, reduced employment, health issues in later life and even early death. We also know that being out of school exposes young people to increased vulnerabilities and risks. Government Select Committees, police chiefs, education unions and many in the charity sector have all spoken clearly about the impact of exclusion and the links to negative outcomes later.

“What should matter is the fact that, whether we can prove the negative impacts or not, we also know we can’t see any tangible benefits either. So, why are we still doing it and what could we do instead?

“Recent months have seen a lot of discussion around supporting young people with their mental health and the part schools can play in a more compassionate post-pandemic world with its priorities realigned. However, early indications are that the rise in exclusions we were already seeing before the pandemic will continue, as schools and students wrestle with the implications of lockdowns, missed schooling and the resulting impact on social skills and relationships.

“Depending on where you look, there is cause for hope as increasing numbers of school leaders move their schools towards a trauma-informed approach to behaviour and a recognition that, now more than ever, exclusion is good for nobody. The ‘zero exclusion’ school is a growing aspiration for leaders and, given that body of evidence that correlates school exclusion with profoundly limited life chances and outcomes, it is fast becoming both a moral and practical imperative for many to reduce exclusion.

“Nonetheless, as is so often the case in our education system, there are some pretty perverse incentives, hoops for schools to jump through and tricky problems for schools to solve if we are to fully capitalise on this mindset shift away from exclusion.

“Very few schools and school leaders have, in my experience, ever wanted to exclude but the pressure to do so is often hard to resist. Unless personally affected (i.e. their child is the one being excluded), parents tend to like exclusion – it is ‘tough’ and signals that their school has ‘high standards’. Equally, governors and other members of the local community are often equally enamoured by strong responses to behaviour issues.

“Of course, some headteachers (only headteachers or those directly nominated by the head are permitted to issue exclusions) resist these pressures and avoid exclusion where they can. However, it takes a very secure headteacher to repeatedly ignore this expectation when governors are her/his boss and so much of a school’s success relies on sufficient ‘bums on seats’ to keep the budget healthy.

“Few things (even academic results in many cases) overcome the ‘playground perception’ that behaviour is bad in a school or that leaders are soft on it and, as such, leaders often feel compelled to flex their muscles in order to ‘impress’ parents/governors who want to believe that this will fix behaviour issues and create a successful school culture. This perception amongst parents and the resulting actions by school leaders are routinely validated by Department for Education pronouncements and guidance on behaviour management which, in recent years, have been widely touted as ‘giving the power back’ to schools to be tough on poor behaviour.

“It is not clear whether anyone asked headteachers if they wanted this power ‘back’. Indeed, had they asked any of the headteachers I know, we would all have said that the blunt tool of exclusion does nothing to change behaviour in a school. Indeed, most would tell you that a positive, supportive culture in a school is much more effective at shaping positive behaviours than any list of reasons to sanction students and the ‘tariff’ to be applied to those reasons! However, I do not recall being sent any updated documents on how to bring more joy, wonder and positivity to my school when I was a headteacher, and I certainly was not afforded sufficient in my budget to train and recruit staff to ensure that students prone to exclusion got the level of support they needed.

“Of course, as well as issues around perception and ‘PR’, these (budgets, staffing and skill levels) are some of the very real practical reasons schools feel compelled to use exclusion. Young people with complex needs can be very challenging in a system which, by design, struggles to truly offer individualised provision. Often, the needs and desires of some young people are at odds with what is expected or asked of them in a normal school environment, and we know, sadly, that young people with additional needs are disproportionately represented in exclusion figures.

“This ‘disconnect’, or misalignment can often be overcome if there is an adult with the time and space to mediate, help the young person adapt or understand, or simply help to remove some unexpected or unforeseen impediment. However, over the last decade or so of flat budgets in schools (IE the same amount of money per student with no increases for inflation or rising costs), the real term reduction in funding that resulted has seen support services, pastoral workers and non-teaching staff in schools become the inevitable victims of belt-tightening. As such, available adults with the time to support the most challenging students have become increasingly rare. At the same time, the specialist training and experience to support the most vulnerable young people – both academically and pastorally – is becoming harder for schools to afford.

“Inevitably, therefore, this creates a ‘perfect storm’ for schools who know that the system is failing these young people and that every exclusion is an acknowledgement of that failure. Nonetheless, they often feel they have no option when they have exhausted the support they can offer within their budget and resources. They are left with the very stark decision of sacrificing the needs of the individual in order to prioritise all other students. This is sometimes the only practical choice and, perhaps it is the inevitable outcome of a comprehensive school system without the money to do what it really wants to, but it rarely feels right or good.

“In this context, the exclusion can be a somewhat desperate signal to the child, the parents, the local authority and the school’s governing body that things are reaching the end of the road and ‘something needs to change here’.

“Couple this with the increased impact of similar pressures on other statutory/support services and the recent rapid increase in mental health and anxiety in young people, and it is fair to say all agencies have been trying to do more with less for some time now. Inevitably in this situation, those at the margins tend to bear the brunt of the problem and, in schools, this means those students for whom additional support might be the difference between successfully completing a lesson and being unceremoniously asked to leave that lesson before conflict ensues and, at times, an exclusion is the result.

“Most good schools are always on the lookout for alternatives to exclusion and there is some really creative thinking going on within many schools. However, the finite resourcing issue rears its ugly head here too; when budgets are tight, it is really difficult for schools to justify disproportionately costly provision for small numbers of young people. For such provision to be successful, it often requires higher staff to student ratios, specialist trained staff and bespoke resources. All of which – of course – add up to greater cost than the school’s standard provision and, crucially, is usually not something that schools can easily predict and budget for in advance.

“Recent years have also seen options for external alternative provision gradually reduce in many areas. In some cases, this was a necessary outcome of increased scrutiny of providers resulting from the controversy over ‘off-rolling’ (the practice of finding ways to remove a student from a school’s roll by means other than permanent exclusion, for the benefit of the school and not the student). However, in some cases, these providers have fallen victim to the ‘trickle down’ effect of budgetary pressures on schools, who can no longer afford to engage the services of external providers for the handful of students who struggle to flourish in the mainstream setting.

“Whilst all of these hurdles and challenges could paint a somewhat bleak picture, schools – and educators more widely – tend to be of an optimistic bent and view this challenge as an opportunity. The necessity to find a solution is, as is so often the way, leading to invention and change that is nudging us towards a brighter future.

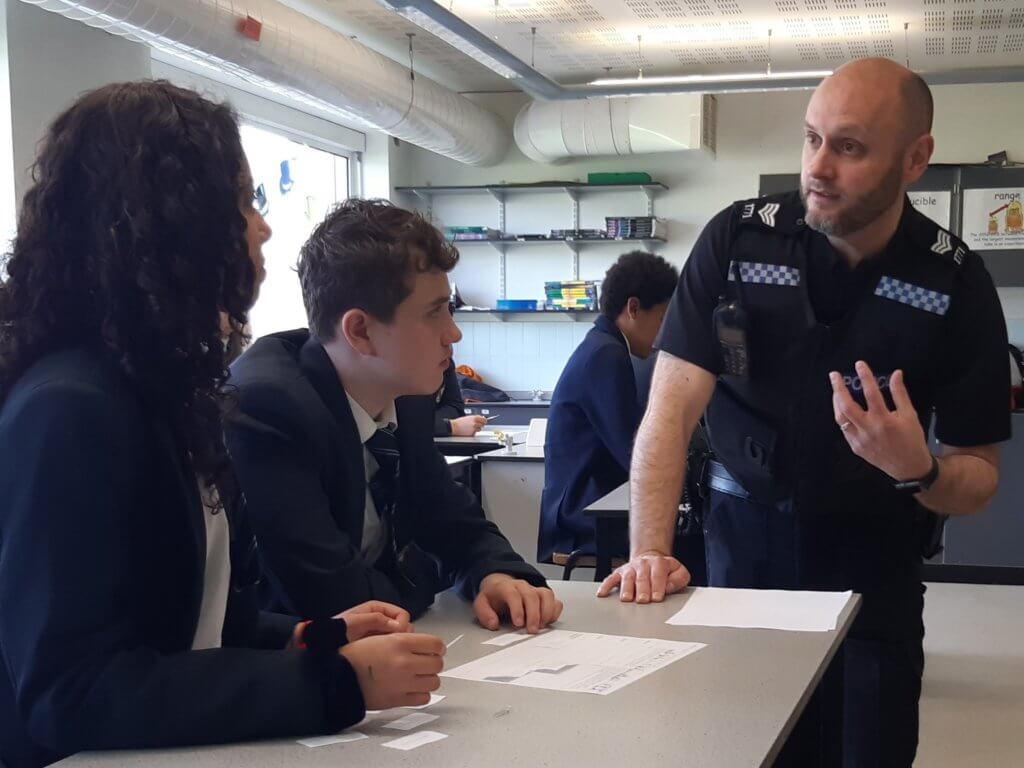

“Several parts of the Thames Valley have recently completed a pilot and subsequent roll-out of a drug diversion scheme that has seen schools and police respectively eschewing exclusion and arrest in favour of a referral into a drug counselling service in cases of drug possession in school. Inevitably, this has led school leaders to consider if there are other community partners/services or approaches that could swing into action in place of exclusion for other ‘offences’ in school.

“Of course, there are always likely to be ‘red lines’ – such as weapon possession or ‘intent to supply’ drugs – where schools and police will have to respond with their ultimate sanction. However, more than anything, this reinforces the need for thoughtful and supportive work with young people earlier on in their journey; that way, those ‘red lines’ never get crossed and the exclusion or the arrest are not required.

“Increasingly, schools do have an understanding of how to change that narrative early, how to avoid young people becoming early victims of exclusion or criminalisation, and how to build resilient communities around our young people but they need support if they are going to be truly successful on the scale that our communities need.

“Whether it be diversion schemes, trauma-informed practice training for schools, reachable/teachable moment mentoring or approved PSHE content provided to schools, there is much already being done to by the Violence Reduction Unit to support schools on this journey in the Thames Valley. Equally, there are many volunteer and charitable organisations working with communities and young people to offer support too.

“However, the rise in exclusion, as well as the ‘mood music’ emanating from the Department for Education on behaviour in schools suggests there remains much work to be done and a need to do it much earlier.

“Much of that work boils down to more schools understanding and accessing the type of support that is available in their community, whether that be funding opportunities, third sector/charity support, social enterprise partners or access to other services with capacity to work with young people. However, with school leaders more stretched than ever and the continuing pressure on schools to be ‘tough’ on behaviour, most schools are not experienced or conditioned in operating another way; put simply, they often do not know what is out there, do not have the knowledge and experience to engage with the range of external services who could support them, and – through no fault of their own usually – are not yet sufficiently trauma-informed in terms of policy or practice to support all students in avoiding exclusion.

“So, rather than blindly ask schools to just reduce exclusion because we ‘know’ the impact it has, we in the VRU are asking ourselves some questions every day: How do we help schools build wide support networks they can access when things get tough with individual young people? How do we build that network of community partners so all schools have access to the best external support for their students? How do we help teachers and school staff understand trauma and shape their internal policies and practices accordingly? How do we win the battle for hearts and minds in the community who so often see this as a school being ‘soft’ or permissive on behaviour?”

If you are a community or voluntary sector organisation and could offer support to young people at risk of exclusion, we’re keen to hear from you. Contact the VRU by email on: violencereductionunit@thamesvalley.police.uk