An Introduction to the Brain Story

This week, Mental Health Awareness Week, we welcome the first guest blog written by Dr Katy Smart of the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford.

I’m very excited to write the first guest blog for the TVVRU website especially during Mental Health Awareness Week. I work in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford where our team have joined forces with the Palix Foundation to share the Brain Story; a narrative to explain the neuroscience of child development and its implications for lifelong mental and physical health. The core story has been packaged into a series of freely accessible resources including animations, learning cards and a self-paced certification course, placing the neuroscience in the hands of front-line workers.

What is the Brain Story?

The Brain Story provides a platform to articulate research which shows how experiences change the way brains are built, and the mechanisms that drive the intergenerational cycle of adversity. This understanding is fundamental to improving long-term mental and physical health outcomes. The Brain Story provides us with an accessible, shared language and a series of metaphors to encourage communication between professionals and individuals on the importance of key concepts in neurodevelopment. The Brain Story draws on the same scientific research as trauma-informed practices; by working together we aim to improve people’s knowledge and understanding of the importance and long-term impact of our childhood experiences. The Thames Valley VRU team have already started the Brain Story Certification course: a free, self-paced, online course delivered by leading experts in the fields of child development and neuroscience.

And why does the development of our brains in early years matter so much?

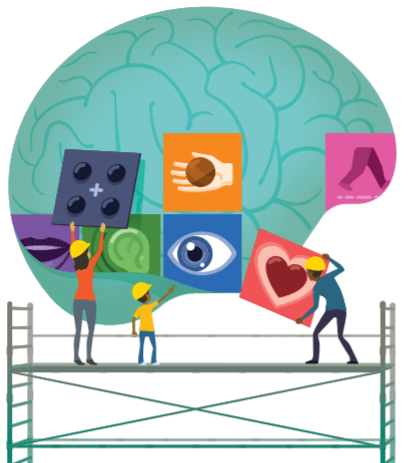

Brain development during childhood is determined by more than just our genes; the experiences we have in the first years of our lives also affect the physical architecture of the developing brain. The brain develops most rapidly during the first three years of life, with a second period of concentrated development during adolescence. The child’s early experiences determine which of the brain circuits are pruned away through lack of use and which ones are reinforced, making the early years vital for children’s longer-term physical, social and emotional development.

A sturdy brain architecture and the impact of adverse childhood experiences:

Responsive adult relationships are one of the key experiences which help the development of a child’s sturdy Brain Architecture. A supportive environment, where ‘in-tune’ interactions take place between the child and the caregiver, provides opportunities for the child to practise basic cognitive, social, and emotional skills and to reinforce the neural circuits fundamental to those skills. In the Brain Story, scientists use the metaphor of “Serve-and-Return” to describe these interactions. In a game of tennis, the child ‘serves’ by reaching out with a look, touch or sound, the caregiver then ‘returns’ the serve in a way that is suitable to the child’s developmental stage, continuing the rally.

However, difficult events during childhood can also adversely affect the development of the growing brain. While some stressful situations, like starting school, or preparing for a test, help a child to learn coping skills, other events can have a long-term negative impact on the child’s brain development. Experiences such as physical and emotional abuse, neglect, caregiver mental health problems, a parent in prison and violence within the household are often called Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs. Research studies have shown that a high ACE score increases the risk of developing physical and psychological health problems later in adulthood. If a child is exposed to prolonged levels of stress, without the assistance of supportive adults to help them manage, then the stressful experience can be termed ‘toxic’. The body’s stress response is designed to be short lived, so persistent exposure to adverse experiences can result in wear and tear on the body, akin to revving a car engine for long periods of time. This can lead to long term physical and mental health difficulties. By understanding the long-term impact of ACEs and Toxic Stress, and the importance of reducing the sources of stress, we are supporting children and adults in promoting good mental health.

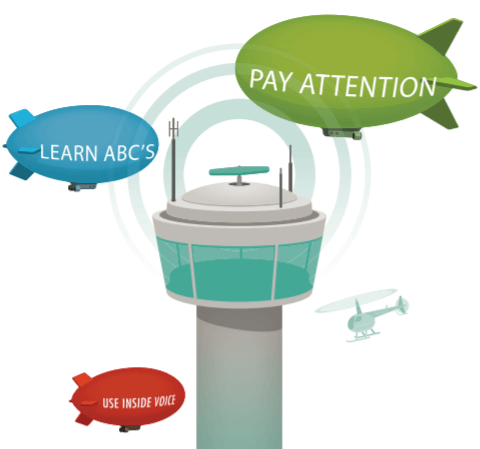

Executive Functions – the “Air Traffic Control” of a child’s brain:

Early adverse experiences can also affect the development of parts of the brain responsible for Executive Functioning. Executive Functioning is used to describe a range of skills which include working memory, mental flexibility, prioritising tasks and ignoring distractions. The Brain Story uses the metaphor of the child’s brain as the “Air Traffic Control” tower at a busy airport; directing and managing the take-off and landing of multiple aircraft, making sure that none of them crash or run out of fuel. These skills are not only vital to children’s school readiness, but are also core, lifelong skills; as adults we need to use our executive functioning to plan ahead, prioritise urgent tasks, think flexibly when situations change and resist temptations. This means that children who experience high levels of adversity may have difficulties with their Air Traffic Control skills, which in turn can elevate the likelihood of risky behaviours such as drug abuse and involvement in criminal activity or violence.

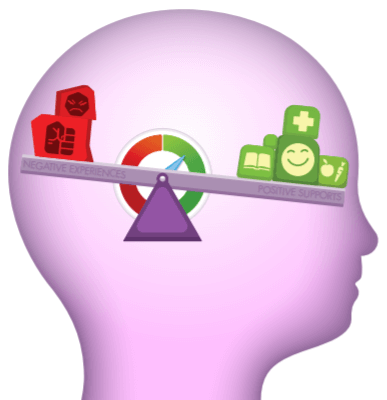

Building resilience:

The metaphor of the Resilience Scale helps us to understand the relationship between experiences and health outcomes. On one side of the balance scales we have protective factors and support, whilst on the other side we have all the experiences that can cause Toxic Stress. A Resilience Scale that is overloaded with negative experiences will tip towards negative outcomes such as anxiety, depression and addiction. Positive experiences and protective factors like attentive caregivers and social supports can offset negative experiences and tip the scale towards positive outcomes. However, genes also play a role in how resilient we are. A person’s genetic inheritance is like the balance point of the scale; this affects how much influence positive or negative experiences have in shaping our life outcomes. The good news is that the position of the balance point is not set in stone and can be shifted through developing key skills and positive experiences which modify gene expression (epigenetics). This means that we can enhance an individual or a community’s resilience by reducing sources of stress, promoting skill development and increasing positive supports.

It is possible to build better brains by exposing children to positive, nurturing interactions from an early age. These positive experiences are the foundation bricks that build sturdy brain architecture, leading to improved physical and mental health throughout life. It’s never too late to change outcomes; using the science to work together will help us enhance long term mental and physical health and reduce the causes of antisocial behaviour, addiction, violence and crime.

For further information on the Brain Story and access to FREE resources and Brain Story Certification course visit our website www.oxfordbrainstory.org and follow us @OxBrainStory. You can contact me via: katy.smart@psych.ox.ac.uk

Dr Katy Smart CPsychol AFBPsS works for the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford. During her career she has consistently worked with children, young people and parents with the aim to improve the lives of children and their families.